The Midnight Sun Film Festival’s prime spot this year is reserved for the screening of Victor Sjöström’s (1879-1960) Ingeborg Holm (1913), a film celebrating its 110th anniversary and “a social cross-section sketched through a woman’s fate, the best film made at that time anywhere in the world” (Peter von Bagh). Marking the beginning of the early golden period of Swedish cinema, this film was the breakthrough and first blockbuster for Sjöström, previously distinguished as the humane man of the theatre stage, but it came about by chance.

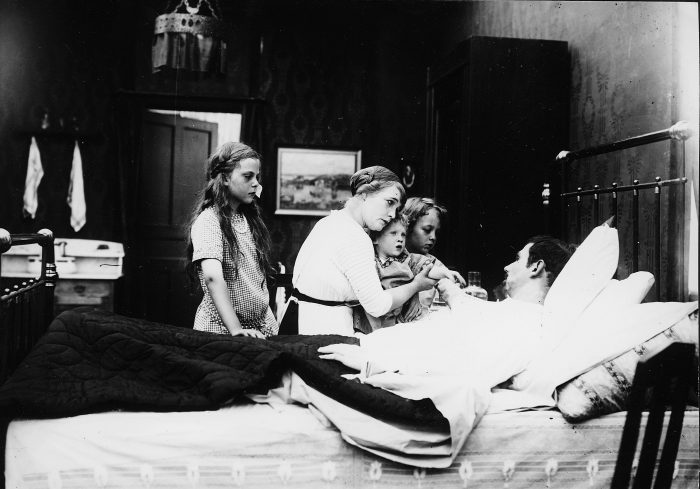

The plot – beware of spoilers! – unfolds as follows: a young mother of three, Ingeborg Holm (Hilda Borgström) and her husband are making plans for the future. A bank has granted them a loan to set up a colonial goods store, and a serene harmony characterises life, until her husband suffers a haemorrhage and dies. An assistant’s frauds bankrupt the shop and, left with nothing, Ingeborg falls ill, is forced to abandon her children to foster homes and ends up in a poorhouse herself. When her young daughter falls sick, Ingeborg runs away to be with her but is taken back to square one. The child dies, and the remaining siblings are brought to visit her. But one of the two no longer recognises their mother, who loses her mind. In the epilogue her adult son, returning from the sea, encounters an institutionalised Ingeborg lost in private delusions, who now fails to recognise her own child. But when the boy shows her mother a photograph from his youth, the unhinged woman’s face lights up with realisation, and the future of the family remains ultimately open.

The most genial insight of this social drama containing intense sociability is the avoidance of emotional excesses. Sjöström transforms the potential exaggerations of melodrama into the clinicality of a “scientific document” (cf. von Bagh), relying on accurate descriptions of people and eschewing theatricality. Mental illness is described not as a “horror effect but as a medical case”, and “the restrained style is the opposite of sensationalist dramas” (Bengt Idestam-Almquist). Ingeborg Holm, praised for its realism and naturalism, can even be seen as the forerunner of The Bicycle Thief (1948), says von Bagh. On the other hand, it strongly foreshadows, for example, John Ford’s many “self-sacrificing mother characters”, Henry King and King Vidor’s Stella Dallas narratives, Joan Crawford’s languishing creations, or Anna Magnani’s thousand-decibel semi-incestual full-blast works.

Ingeborg Holm can, of course, be accused of conservatism –something at least, if not a lot, has happened in the last hundred years regarding gender equality – but in relation to the conventions of its time, Sjöström’s vision is both vibrant and modern. To quote von Bagh again, “Ingeborg Holm is in a perfect position when we try to choose the first complete metric – that is, over an hour long – landmark work in the history of cinema.”

The music is composed by a duo who have long collaborated musically, Matti Bye, a favourite of the Midnight Sun Film Festival audience and one of Sweden’s most renowned film composers, and Lau Nau, the Finnish experimental music artist, singer-songwriter, and composer. They will perform as a trio with cellist Leo Svensson at the screening.

Lauri Timonen