When it comes to quality and pace, Milanese director Michelangelo Frammartino is in the same class as veteran masterpiece-maker Victor Erice. Frammartino could be likened to many of the greats of film history while still being firmly in his own league. His seemingly modest filmography is a prism into humanity, larger than the sum of its parts. In his films, the symbiotic natural relationship between humans, flora, and fauna – but also the decay of that relationship in the modern world – are central. The sturdy landscapes and forgotten villages of Southern Italy set the stage.

Frammartino, who finds his niche somewhere between documentary film-making and art installations, began his studies in architecture but later made the switch to the film school of Civica Scuola di Cinema. Stylistically, Frammartino is one of the vivacious reformers of Italian cinema. His hybrid style has similar observational notes as the award-winning films of Gianfranco Rosi and Pietro Marcello, and a love for a more diverse Italian imagery, as in works by Ermanno Olmi or Alice Rohrwacher.

Though he comes from industrialised and urban northern Italy, the director often turns his gaze south, to his grandparents’ Calabria. His debut film The Gift (2003), which has also graced Finnish TV screens in the past, tells the interwoven stories of an old man and a young girl in a remote Calabrian village, whose winding roads call to mind the rural landscapes of Abbas Kiarostami. Shipwrecks and decaying cars mirror the forgotten Italian south and the passage of time. Erosion and wind have hardened the rocky village, but that hasn’t dampened the desires or humanity of the townspeople. Frammartino’s film is, in and of itself, a little gift to the viewer.

The director’s international breakthrough and one of the masterpieces of modern filmmaking, The Four Times (2010) depicts the wayward journey of the soul or the spirit from one body and form to another, both poetically and irresistibly cinematically. It is hard to imagine how a film, which deals meditatively with themes of rebirth, can also seamlessly draw from the wordless comedy of Tati and Chaplin, but this is something one must witness for oneself. The film had its premiere in the Quinzaine des réalisateurs section at Cannes, where the central dog won the Palm Dog award for the best canine performance.

Loyal followers of Frammartino had to wait more than a decade for his next work, but it was well worth the wait. The partially documentary-style The Hole (2021), which had its debut at the Venice Film Festival, is set in the early 1960s and at the peak of the Italian economic boom. While Europe’s tallest building is being built in northern Italy, a small group of researchers are descending into the world’s third deepest cave in the south. The film depicts both the descent of the research team as well as the everyday life of a nearby town. In the beginning, the camera steps out into the light as from Plato’s cave, but true knowledge is found by delving back into the depths. Icons of the time and magazine cover stars are ephemeral dust before the mysteries of the universe.

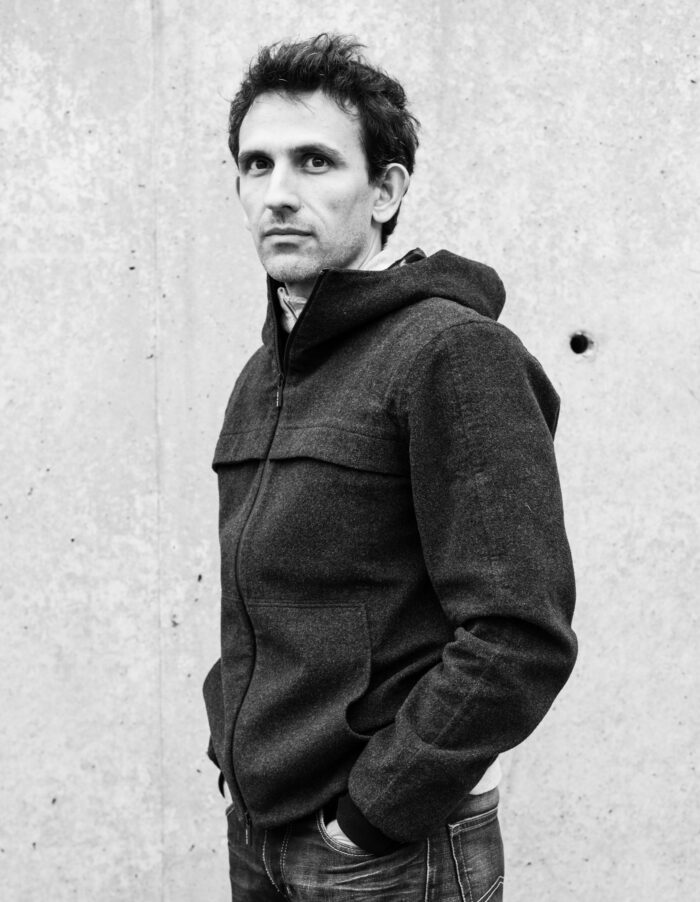

Otto Kylmälä