Few and far apart are the filmmakers who surprise you with every new film, yet make you feel at home from shot one each and every time. Mexican grandmaster Arturo Ripstein y Rosen is one of that small band of cinematic adventurers, pathbreakers, inventors of forms, revisers of genres, stories, tropes – whose work is an invitation to a grand journey into the farthest shores of the human mind and soul.

Ripstein’s massive œuvre contains seemingly everything: from adaptations of literary classics (eg. Elena Garro’s Los recuerdos del porvenir in 1968; Juan Rulfo’s El gallo de oro as The Realm of Fortune in 1985; Gabriel García Márquez’s No One Writes to the Colonel in 1999); via documentaries like the short Salón Independiente (1969; together with Felipe Cazals & Rafael Castanedo), a jazzy record of an exhibition that became a seminal event in the history/development of modern Mexican art, or Lecumberri, el palacio negro (1976), about the last months of a prison in Mexico City; to genre pieces like his fiction feature debut, the sarcastically melancholic, honed-to-the-bone western Time to Die (1966), or the edgily moody exercise in Mexican Gothic, La tía Alejandra (1979), let alone the at times deliciously silly comedy The Ruination of Men (1999).

One might say that this is an intellectual and spiritual vastness, an idea of diversity, of cinema’s ability to talk about everything to everybody that Ripstein was born into. For his father, Alfredo Ripstein hijo, was a producer and key figure of Mexican cinema’s so-called Golden Age, who financed artistic enterprises as diverse as Julio Bracho’s Dumas fils-based melodrama La mujer de todos (1946) and Alejandro Galindo’s enchanting juvenile delinquency-meta-movie Mañana serán hombres (1961), or his son’s capital Naǧīb Maḥfūẓ adaptation The Beginning and the End (1993) and several groundbreaking horror films by Fernando Méndez. Which is to say that in Ripstein’s filmmaking, that best and brightest of classical Mexican film culture remains present and urgent – reinvented on some formal levels, unchanging in its curiosity and generosity.

Lively and sparkling adjectives for an opus ripe with morbidity and anguish, absurd humor and grotesque drama, desperate stabs at happiness and agonizing twists of fate! Already his debut circles around the question of destiny: Does a violent death have to be avenged (especially when it turns out that matters were a bit different than originally believed to have been…)? In The Castle of Purity (1972), a man keeps his whole family prisoner to protect them from a world he deems simply evil – while Lecumberri, el palacio negro begins, irony of ironies, with the aftermath of a prison break. The Holy Office (1973), then, investigates the Spanish inquisition’s antisemitism in a surprisingly detailed way, with the cleric-investigators and -judges shown more as bureaucrats – who in a certain way fail to save their victims, as they (decide to) die for their faith; the latter is of particular importance for Ripstein, as his family descends on the paternal side from Jewish Poles who fled to Mexico.

These are all, mind, early works that with deft strokes delineate Ripstein’s key concerns, which he’s been working through in always perplexing and sometimes disturbing ways ever since. The deeper one dives into Ripstein’s world, the more extraordinary the view of the gardenia-scented abyss that is his cinema becomes: Rarely looked tenderness as gregarious, truth as grim, mankind as jolly, weird, glorious, horrifying and yet worth saving, putrid and clumsy like the bodies we’re caught up in, yet finally resplendent like the sun, for even the lowest sinner has their moments of wisdom and beauty.

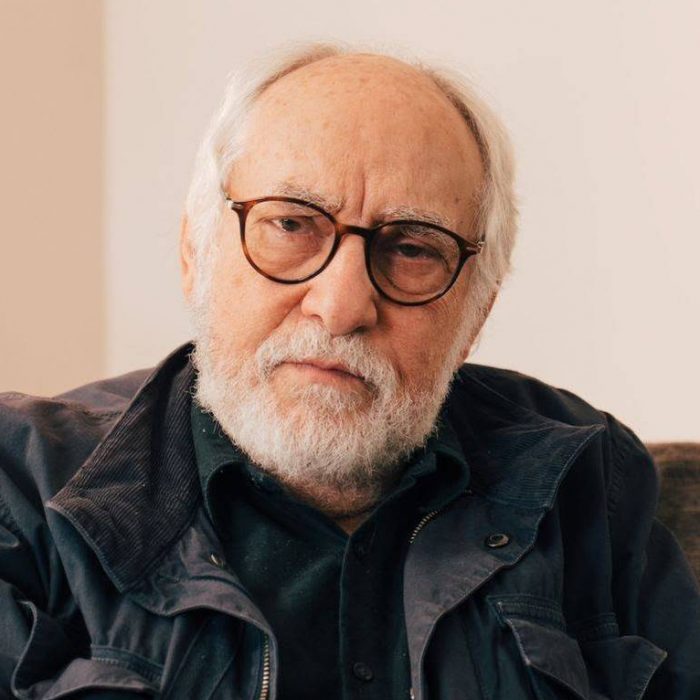

Olaf Möller