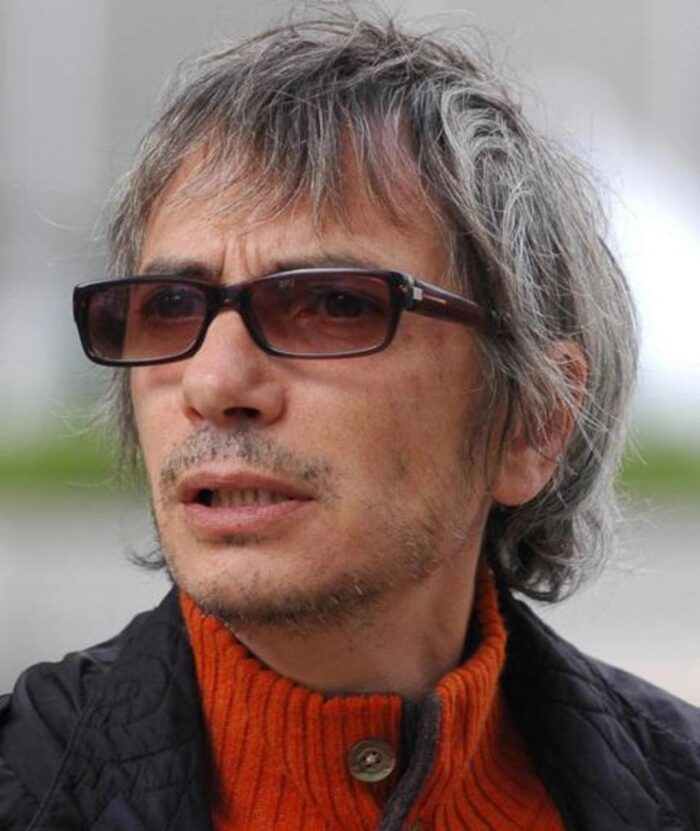

One of the last true representatives of the European auteur tradition, director-writer Leos Carax (Alex Christophe Dupont) was born in Suresnes, a western suburb of Paris, to two journalists – a French father and an American mother. Carax, who also carved himself a career as a critic – his stage name is an anagram of the words “Alex” and “Oscar” – made his first short film, Strangulation Blues, in 1980, and his debut feature Boy Meets Girl (1984), shot in black and white, made well-deserved waves four years later. Interpreted by his future trusted actor Denis Lavant and Mireille Perrier, this melancholy love story contains, alongside homages towards Godard and Truffaut, many of the essential hallmarks of Carax’s art: the beauty of gestures, romantic chaos, intuitive imaginative physicality, melancholic wanderings on the nocturnal shores and bridges of the Seine that grow into the director’s soul-scape, jerky lyricism marked by adrenaline rushes, unexpectedness that breaks the conventions of form, and hallucinatory imagery that leans on surrealism…

Borrowing its name from a poem by Rimbaud, Bad Blood (1986) marked his definitive breakthrough, growing into an autopoietic, brutally romantic genre collage characteristic of Carax. Equally sensitively fierce, unconditional, and headstrong is The Lovers on the Bridge (1991), which expands into a cruel adult fairy tale. It promptly received an inordinate amount of flak for, among other things, its budget, which the French press raised to mythical proportions and deemed to be Ciminolian. Associated together with Luc Besson and Jean-Jacques Beineix as a representative of the ’80s Cinéma du look movement, Carax’s influences range from Robert Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer (1971), set on the very same bridge, all the way to Jean Vigo’s L’Atalante (1934). Nor is it likely a coincidence that Jack and Rose (in a direct reproduction of the final scene) pose in the bow of Titanic (1997), or that Uma Thurman’s tracksuit in Kill Bill (2003-2004) is bright yellow, reminiscent of Juliette Binoche’s character as signs of the opposite cultural exchange.

The next directional work by this artist known for his long breaks, Pola X (1999), a rough adaptation of Herman Melville’s novel Pierre: or, The Ambiguities (1852), acts as a kind of private cleansing ritual – a cyberpunk hybrid of Evelyn Waugh’s Brideshead Revisited (1945) and Jacques Rivette’s urban board games. The exploding cemeteries in the first shots seem to pose the unspoken question – can the dead be killed again? – and on a meta level, the sense of a ghost story is deepened by the early demise of both main actors.

Carax took his time again, directed short films and Godardian postcards like Sans titre (1997), music videos for Carla Bruni (2002-2003) and New Order (2005), and a guerrilla-style episode of the portmanteau film Tokyo! (2008). The latter introduces us to Denis Lavant’s incredible acrobatic-anarchist creation belonging to the series of “sacred beasts,” the metropolis-terrorising Monsieur Merde. Dressed in a green suit and living in the sewers, the dark side of Chaplin’s Tramp is a brilliant combination of a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle, the sadistic but lusty Opale from The Testament of Dr. Cordelier (1959), the persecuted Godzilla, the hedonistic King Ubu, and the tormented Jesus Christ. The character also makes a comeback in Holy Motors (2012), one of the masterpieces of the 21st century by any measure.

Carax’s first English-language film Annette (2021), a lively collaboration realised with the cult band Sparks combining musical and rock opera genres, once again opens unknown doors while cleverly tapping into the universes of his earlier works. His latest directorial effort, the 41-minute It’s Not Me (2024), premiered at the Cannes Film Festival this spring.

Leos Carax is a visionary who never explains his signals and the greatest French cinematic artist of his generation, who has refused to ever forget that the camera-pen was invented for poetry. When the chain-smoking maestro with already two nicotine patches stuck to his throat (according to legend) lights his next cigarette, not only does its fiery tip begin to glow, but so do the projector lamps, the cosmic screens, and the audience’s imagination!

Lauri Timonen