The universe is a big place—a fact that can instill fear, provoke awe, change perspectives, and expand understanding. The latter three are the focus of the book Cosmic View (1957) by Dutch educator Kees Boeke. His work inspired two films in 1968: Cosmic Zoom, by Eva Szasz, and Powers of Ten, by Ray and Charles Eames (though their 1977 version is better known). Cosmic Zoom begins with a boy and his dog rowing on the Ottawa River, moving into a hand-drawn animated zoom out into the galaxy before plunging back to the boy. In distinction to Powers of Ten, Scasz’s film does not merely delve into the molecules of the boy’s hand, but zooms into the boy’s blood cells as a mosquito is drinking them in. This is a fascinating choice, as it introduces an essential idea into the contrast between microscopic and galactic scales: that of contact. The outlook we get from the film is not just about how incredibly vast the universe is—both outside and inside of us—but also that we share it with so many invisible beings. Even creatures we find distasteful—mosquitos—can be the subject for enlightening reverie. The films in this program all perform a cosmic zoom—moving us through space and time, shifting us from one point of view to another, calling attention to what we missed, and refocusing our vision of the present in relation to the future and past.

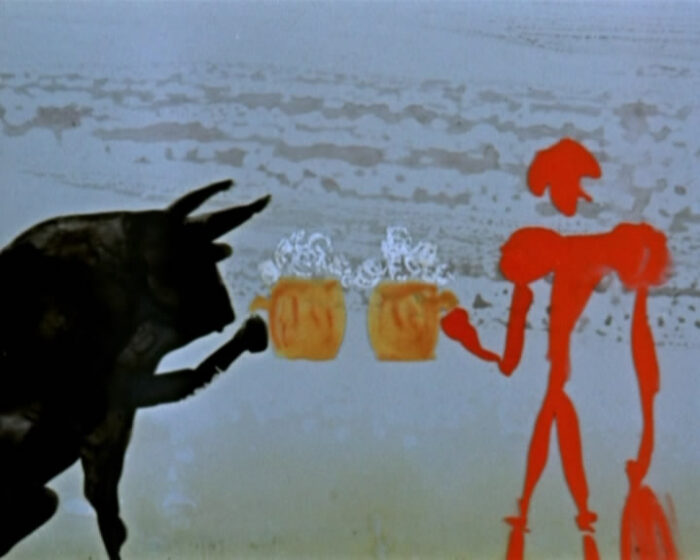

Alla Grachyova’s Autumn Fishing (1968) and Jean-Pierre Rhein’s The Little Bird Who Wanted to Be a Motor (1971) feature little creatures moving from the minute to the celestial, zooming slowly between dandelion fluff and stars and cicadas and airplanes. In A Place on the Streetcar (1979), György Csonka zooms across time from the confined space of a streetcar, giving us a metaphor for the way we move through life—with a limited view of the major events affecting us. Jan Lenica’s A (1964) performs a kind of dolly zoom—creating a disorienting sensation of impossible movement as the letter A distorts the space around it. The letter signifies a world we desperately seek to understand and control—but solving one mystery only prompts another to appear. Heino Pars’ Nail (1972) also focuses on the symbolic realm, using a mundane object as metaphor for the mysterious nature of our relationships. In Red and Black (1963), Witold Giersz gives us witty meta commentary about conflict as performance, zooming back and forth between enemy perspectives as well as highlighting a rack focus between reality and art.

Jaromir Wesely’s What Happened Then? (1994) is an adaptation of Tove Jansson’s book, which also plays with focus, adjusting our attention from one moment in time to another. As with fairy tales, a seemingly routine journey to bring home milk zooms us into the sublime, because while the vast forest surrounding us is unknowable, the abyss within—whether it is a wolf or a vacuum cleaner—is both finite and infinite. Thus, the Moomins discover the familiar in the strange, nudging us away from fear towards a courageous yes to cosmic peace, love, and understanding.

Jennifer Lynde Barker

Screening duration: 70 min

Curated by: Jennifer Lynde Barker

ELOKUVAT

A (West-Germany, 1964)

A Place on the Streetcar (Hungary, West-Germany, 1979)

Autumn Fishing (Ukraine, 1968)

Cosmic Zoom (Canada, 1968)

What Happened Then? (Sweden, 1994)

Nail (Estonia, 1972)

Red and Black (Poland, 1963)

The Little Bird Who Wanted to be a Motor (France, 1971)