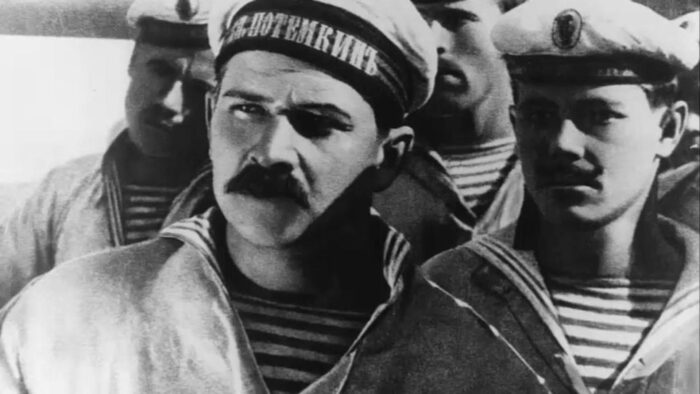

Battleship Potemkin has equally been regarded as the mother of all propaganda films and a masterful depiction of how the grinding down of humanity sparks a rebellion that eventually forms into a revolution. Those who delve into film scholar Lauri Piispa’s newly released opus Eisenstein (Helmivyö 2025) will likely end up leaning towards the latter interpretation.

Potemkin was a made-for-hire project, one of the artworks commissioned for a 1925 gala at the Bolšoi theatre celebrating the revolution of 1905. The unrealistic production schedule resulted in a creative solution – a single episode in the script depicting the Potemkin uprising was stretched out into a feature-length metaphor for the year of the revolution. The iconic Odessa Steps sequence never took place in reality, but it is based on St. Petersburg’s “Bloody Sunday”, the real-life massacre of unarmed protesters that sparked the revolution in 1905. Happy accidents and a fearless sense of experimentation moved the project along, and the final product captured something extraordinary.

Contributing to Potemkin’s revolutionary nature is the film’s use of montage, which has been compared to cubism. The montages feature consecutive shots from varying angles, they stretch time and have the ability to make a single moment feel emphatically meaningful. The flag raised above Potemkin represents a revolution of freedom, fraternity and equality – individual people uniting in a cry for human rights, against oppression.

Mia Öhman