When Brazilian Karim Aïnouz recounts his life as a boy in Fortaleza coast town and later as a cosmopolitan filmmaker, one topic keeps repeating: his warm respect towards his quick-witted mother who worked in a university.

His single mother was there when Aïnouz first visited the cinema of his home town, where he saw the lively John Travolta sliding through the dance floor in Saturday Night Fever (1977). The memory makes the director laugh. On closer inspection the effect of that scene sheds light to his entire body of work.

Lead by a military junta, the Brazil of Aïnouz’s youth was a country where telenovelas of big emotions filled television channels. There was no local film culture, apart from few imported films. Aïnouz said that telenovelas were clearly made to tame people and keep them in their homes.

“We saw posters that said ‘Love Brazil or leave Brazil’. It was interesting to grow up in those circumstances, although horrible from the country’s point of view.”

Aïnouz’s family was upper middle-class even after the engineer father left them. Studying was encouraged and the leftist family didn’t hesitate to criticize the society. Making films for a living didn’t even cross Aïnouz’s mind, for there were no role models for that and there was no market or funding for domestic films. The boy was interested in mathematics and sociology, even leaving a mark on society as a politician. His mother, a biochemist, stated to this that “sociology isn’t a serious subject!”

Aïnouz is often asked about the events that led him to study architecture as a teenager and eventually to New York to study a master’s degree as a 21-year-old. He indeed was brought up in the influence of architecture, but according to Aïnouz himself he drifted to it. It is apparent that the multi-talented young man had many options to change the world and selected the one that fascinated him most.

Life in New York in early ’90s was an environment that enabled pleasure seeking and experimentation. As a gay man coming from “small” Fortaleza he welcomed the liberating change of environment. The experimental American film scene grabbed onto social questions with passion and it was a fertile soil for the LGBTQ+ community.

New friends, the home street film laboratory and film rental shop Kim’s Video led Aïnouz to the world of cinematic storytelling, celluloid and Super 8.

Aïnouz’s view of cinema changed when he saw Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story (1987) by Todd Haynes, a film that starred Barbie dolls. Would it be possible to make a film with such a low budget? Aïnouz marched to Haynes’ apartment in Brooklyn straight away and got himself a job in the production team. The rest is Brazilian and LGBTQ+ cinema history. Nowadays Aïnouz is one of the most celebrated names in Brazilian film culture, a visible dismantler of the patriarchy and a proponent of dance and love. In his debut fiction film Madame Satã (2002), ten years in the making, the camera movement occasionally resembles dancing.

The discussion ends with a memory from the summer of 2019, when Aïnouz’s The Invisible Life of Eurídice Gusmão (2019) was shown in MSFF program. According to an anecdote the audience was so moved that a puddle of tears had to be mopped off the cinema floor. The film is homage to the generation of the director’s mother and grandmother.

But which movie would Karim Aïnouz take to a deserted island? Querelle (1983) by Rainer Werner Fassbinder.

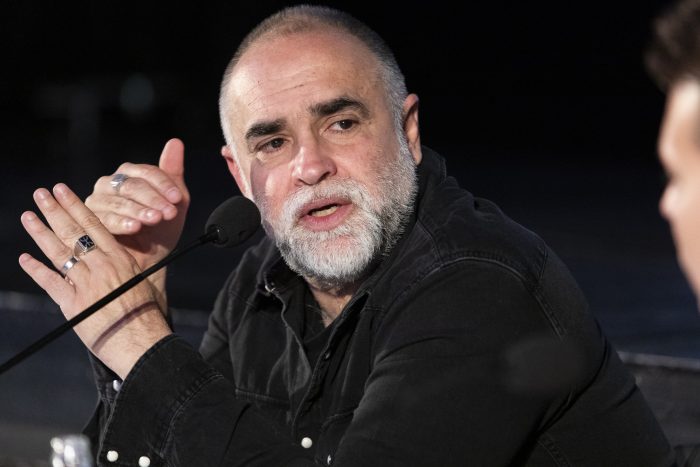

Photo: Viena Kytöjoki